Measles

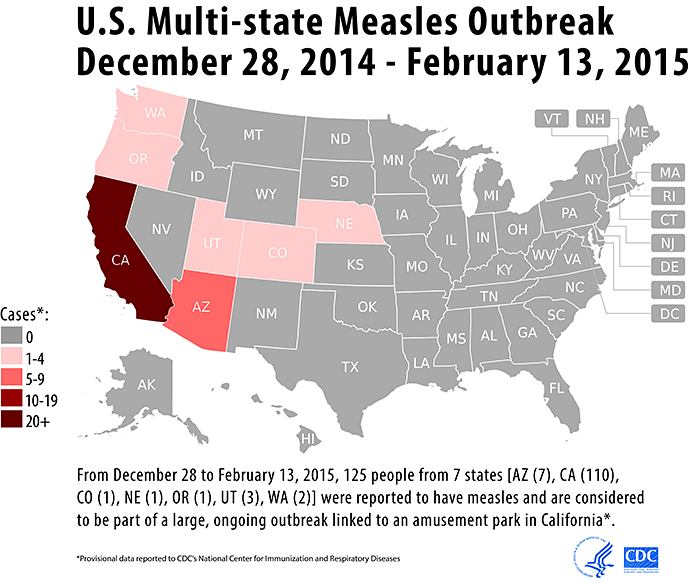

The recent measles outbreak that originated in California's Disneyland has caught the attention of the public, the media, and government officials and raised ethical questions about vaccination policies across the country.

Why do we keep vaccinating against measles?

Measles has been very rare in the United States for the past 20 years, with fewer than 1000 cases annually, but globally measles remains one of the major killers of children. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 145,700 children died from measles in 2013. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) project estimates a lower number of about 95,600 deaths. But even that lower number represents a huge tragedy: it means nearly 100,000 babies and young children are dying every year from a vaccine-preventable infection. About 1 or 2 children die out of every 1000 children infected with measles—or more, in places where many children are undernourished and vitamin A deficient—which means that millions of people around the world still contract measles each year.

Suppose that the United States stopped vaccinating against measles. What would happen? Because of cases imported by international travelers, measles would quickly return to America. Measles is one of the most contagious viruses. About 90% of people not immune to measles will become infected if they are exposed to someone with measles. If a large proportion of children in the U.S. were not protected by immunization, measles would rapidly spread across the country. And some of the children who became infected would die.

We can estimate the number of deaths that would occur if we stopped vaccinating by referring to data from the U.S. before the MMR vaccine was widely used. In 1960, there were more than 500,000 cases of measles and about 450 measles-related deaths. Since the population of children less than 5 years old is about the same—about 20 million—now as it was in 1960, we could expect 450 measles-related deaths per year in young children. And thousands of children might survive measles but be left with blindness, hearing loss, or learning disabilities due to measles encephalitis.

And the number of deaths might be higher than 450 now. Modern medical advances keep kids with serious illnesses alive (thankfully), but they also have led to increased numbers of children who are immunocompromised due to cancer treatment or other medical challenges. Some of the most poignant pleas for parents to vaccinate their kids against measles is coming from the moms and dads of children with life-threatening diseases. Their children are at risk of dying because they cannot be vaccinated against measles. They must rely on “herd immunity,” the protection everyone gets, especially the most vulnerable, when the vast majority of the population has been vaccinated.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recently launched a new measles website. Adults who are not sure of their vaccination status and parents who have questions about childhood vaccinations can check out the scientific information provided there. It is always advisable to consult with a primary care provider or a pediatrician about preventive health options for individuals and families, but the general recommendation is for children to receive a first dose of MMR vaccine at 12-15 months of age and a second dose at 4-6 years of age. International travelers can have a blood test to check their immune status and confirm that they are protected before their trips so they will not bring measles home with them as an unwelcome souvenir. Measles can be a very serious infection, and vaccinations save lives.

Dr. Tony Yang

Dr. Tony Yang is a George Mason University’s College of Health and Human Services researcher whose work in health policy and law has begun to understand the contributions of these exemptions on disease outbreaks. Dr. Yang’s work is helping to provide evidence-based information about current laws and public health implications. His most recent article provided a toolbox for legislatures to understand the policy options and potential impacts of allowing nonmedical exemptions for vaccination requirements. Click here to read Dr. Yang's most recent article.

Peer-Reviewed Articles

Yang YT, Silverman RD. Legislative Prescriptions for Controlling Non-medical Vaccine Exemptions. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) 2015;313(3):247-248.

Orenstein DG, Yang YT. From Beginning to End: The Importance of Evidence-Based Policymaking in Vaccination Mandates. Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 2015 (in press).

Yang YT, Debold V. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Effect of Non-medical Exemption Law and Vaccine Uptake on Vaccine-Targeted Disease Rates. American Journal of Public Health 2014;104(2):371-377.

Viewpoints

Yang, YT. (2015). Why Mississippi Hasn’t had Measles in over Two Decades. The Conversation.

Yang, YT. (2013). Non-Medical Exemptions: Weighing Public Health and Individual Rights. Harvard Law.

Dr. Yang quoted in the article, "Making a case for stricter exemptions for childhood vaccinations" by Jamie Rogers

Information about Dr. Yang received from CHHS.